"Should I use Skills or MCP?"

"What's the difference between Skills and Subagents?"

"Where do I put my instructions—CLAUDE.md or a Skill?"

If you've worked with Claude Code, you've likely asked these questions. You're not alone—these primitives can seem like competing options, and choosing among them is a common source of confusion. Anthropic has published explainers to clarify how they relate. This article offers a different lens.

You're asking these questions because you want Claude Code working harder for you. The building blocks—Skills, Commands, Hooks, MCP, Subagents, Plugins—serve different purposes, and understanding which is which is how you unlock that power.

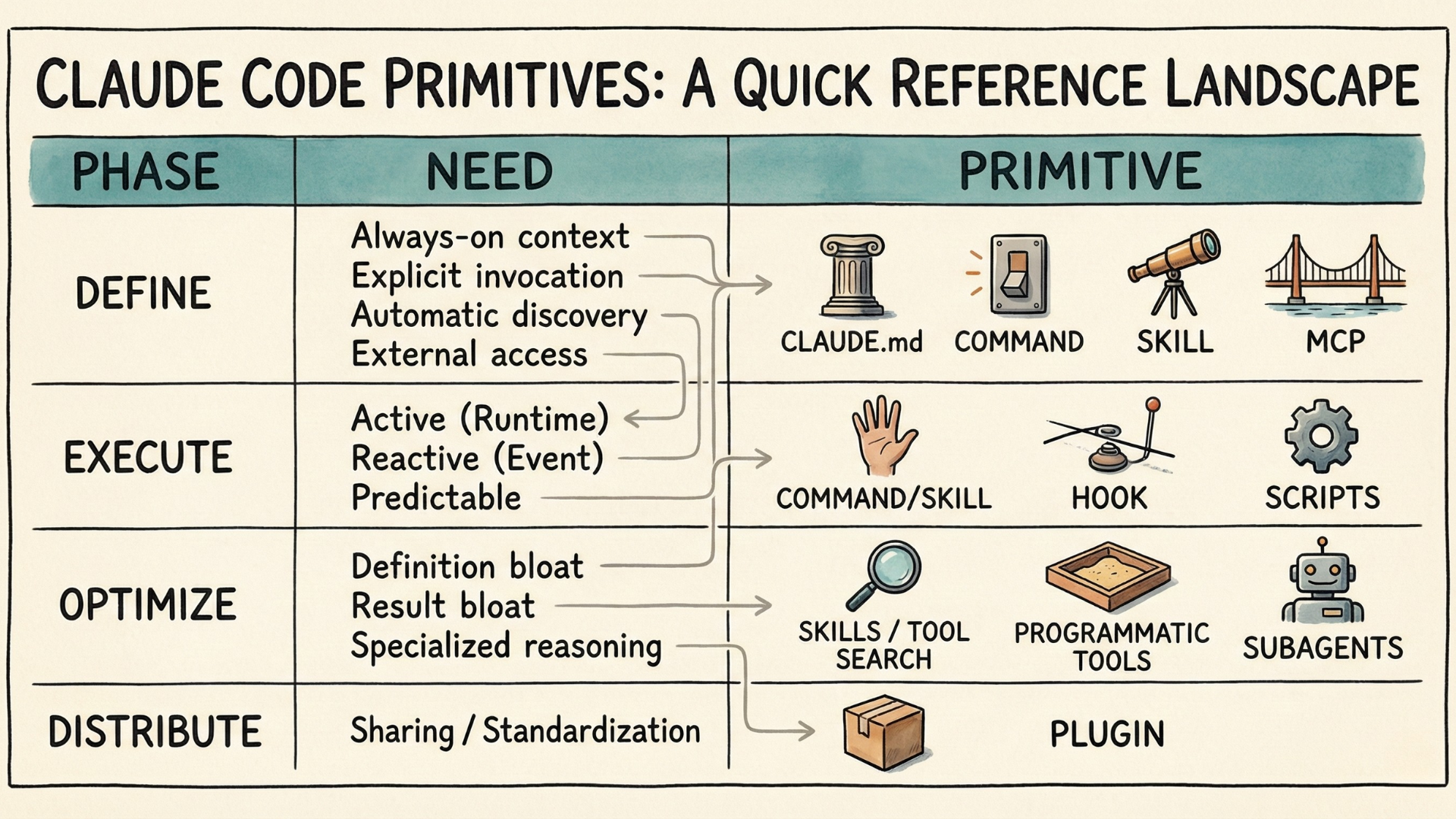

If you look at them through what I call the Agent Capability Lifecycle, things become much clearer. These are the four phases:

- Define — What should Claude do?

- Execute — How should it run?

- Optimize — How do you make it efficient?

- Distribute — How do you package for others?

You'll encounter these roughly in order—you can't optimize what you haven't defined—but you'll often circle back as your project evolves. The questions that opened this article become easier to answer once you see which phase you're in.

Claude Code keeps evolving—Commands, Hooks, Subagents, and most recently Skills and Plugins. As new features appear, the Capability Lifecycle will help you understand where they fit—or recognize when something genuinely new has arrived.

Define: What Should Claude Do?

You want Claude to do something. Often, you can just ask—Claude has built-in tools for reading files, writing code, running commands. You describe what you need, Claude figures it out. Done.

But sometimes "just ask" isn't enough.

You want consistency. You have a specific code review checklist, a particular commit message format, a defined process you want applied the same way every time. You don't want to re-explain it every conversation. You don't want to risk forgetting steps.

You need external access. Claude needs to reach a system it can't already access—an API, a database, a third-party service.

These needs lead to different Claude Code primitives.

When You Want Consistency: CLAUDE.md, Commands, and Skills

If you find yourself giving Claude the same instructions repeatedly, save them. The question is: when should they load?

CLAUDE.md provides always-on context. Instructions here load at the start of every conversation—your project standards, coding conventions, key architectural decisions. This is the right place for foundational context that applies everywhere.

Commands—Claude Code's slash command feature—load when you invoke them. A command is a markdown file containing instructions. Type /review and your code review checklist loads. You decide when; everything loads at once.

Commands work well for short, focused instructions you use repeatedly. But they have limits: everything loads upfront, and you must remember to invoke them.

Skills are the comprehensive approach. A skill is a modular package that bundles everything needed for a capability—instructions, code, reference files, even tool definitions. Skills can transform Claude from a general assistant into a specialist for your specific domain.

Skills differ from commands in two key aspects:

- First, Claude discovers relevant skills automatically based on what you're asking. You don't type

/skill-name—Claude recognizes that your request matches a skill's description and applies it. - Second, skills use progressive disclosure: a brief description loads always, detailed instructions load when the skill activates, and reference material loads only when needed. This means skills can be comprehensive without bloating every conversation.

Skills have another advantage: portability. Because Skills define what expertise exists—not where to execute them—the same Skill works across different execution contexts. A Skill runs the same whether Claude uses it in the main conversation, delegates it to a subagent, or invokes it through code execution. This helps Skills to become an open standard—Skills written for Claude Code can work with other platforms that adopt the specification. And that is already happening: OpenAI's Codex CLI now supports Skills with the same SKILL.md format and progressive disclosure, and GitHub Copilot automatically loads Skills from your .claude/skills directory. The capability you build once works across agentic tools.

How do you choose? Use CLAUDE.md for foundational context that applies everywhere. Use Commands when you want explicit control over when instructions load. Use Skills when you want Claude to recognize relevance automatically, or when your capability is complex enough to benefit from progressive disclosure.

When You Need External Access: MCP or Direct Integration

If Claude needs to interact with systems it can't already reach, you need to provide a tool as a bridge between Claude and the external world. The simple and traditional way is to define the tool as a function with signature, parameters, and make it available to Claude, e.g., through a file system. If you want more reusability, you can use MCP (Model Context Protocol) to supply tools. This is particularly valuable when you're connecting many services—each follows the same MCP patterns.

It is easy to confuse MCP and Skills as both of them seem to provide tools to the agent.

MCP standardizes how agents connect to external services. Instead of building custom integration logic for every API, you configure an MCP server, and Claude can access its tools through a consistent interface. On the other hand, Skills standardize _how_ agents load and use capabilities—progressive disclosure and context efficiency. So they belong to different dimensions.

You can use Skills with MCP servers (wrapping them in skill definitions), or without MCP—using direct API integrations, local code libraries, Bash tools, or virtual environments with filesystem access. The skill format is agnostic to the underlying tool implementation.

Therefore, an example setup could be: MCP connects Claude to your database. A Skill teaches Claude your schema, query patterns, and best practices. The MCP server provides the connection to tools; the Skill provides the expertise of leveraging them.

In short, Skills and MCPs are complementary, they solve different problems and neither depends on the other—but they strengthen each other.

Execute: How Do You Run It?

You've defined a capability, possibly as a portable agent skill. Now: how does it actually run?

Two questions determine execution: when does it trigger, and how predictable is the behavior?

Active vs Reactive: When Does It Trigger?

Most of the time, you or Claude decide at runtime. You type /commit and your workflow runs. You ask Claude a question and it decides to call the relevant tools if needed. This is active execution—a runtime decision triggers the action.

But sometimes you want things to happen only when certain events occur. Every time you edit a TypeScript file, formatting should run. Every time Claude is about to remove a directory of files, you want an extra check. You want them automated. This is reactive execution—events trigger action, and you pre-configured which events matter.

Hooks enable reactive execution. Claude Code supports hook events spanning the full session lifecycle: session start and end, before and after tool calls, when you submit a prompt, when Claude finishes responding, and more.

Active execution is the default pattern—and probably sufficient most of the time. But if you need certain actions triggered by specific events, hooks come in handy.

Deterministic vs Non-Deterministic: How Predictable?

Here's the subtlety: not all execution is equally predictable, and this applies to both active and reactive execution.

Deterministic execution behaves identically every time. For active execution, this means pre-written scripts you invoke—same input, same output. For reactive execution, this means command hooks, which execute bash scripts on every trigger. Use deterministic execution when consistency is non-negotiable: formatting rules, validation checks, compliance requirements.

Non-deterministic execution may take different paths on different runs. For active execution, this is Claude's normal orchestration—flexible, adaptive, capable of handling novel situations. For reactive execution, you have prompt-based hooks which invoke an LLM to make decisions. Use non-deterministic execution when you need flexibility and judgment—just expect variation.

Optimize: How Do You Make It Efficient?

You've got capabilities defined and running. Then you add more. And more. And suddenly conversations are sluggish, your context window is filling up before you've done anything useful.

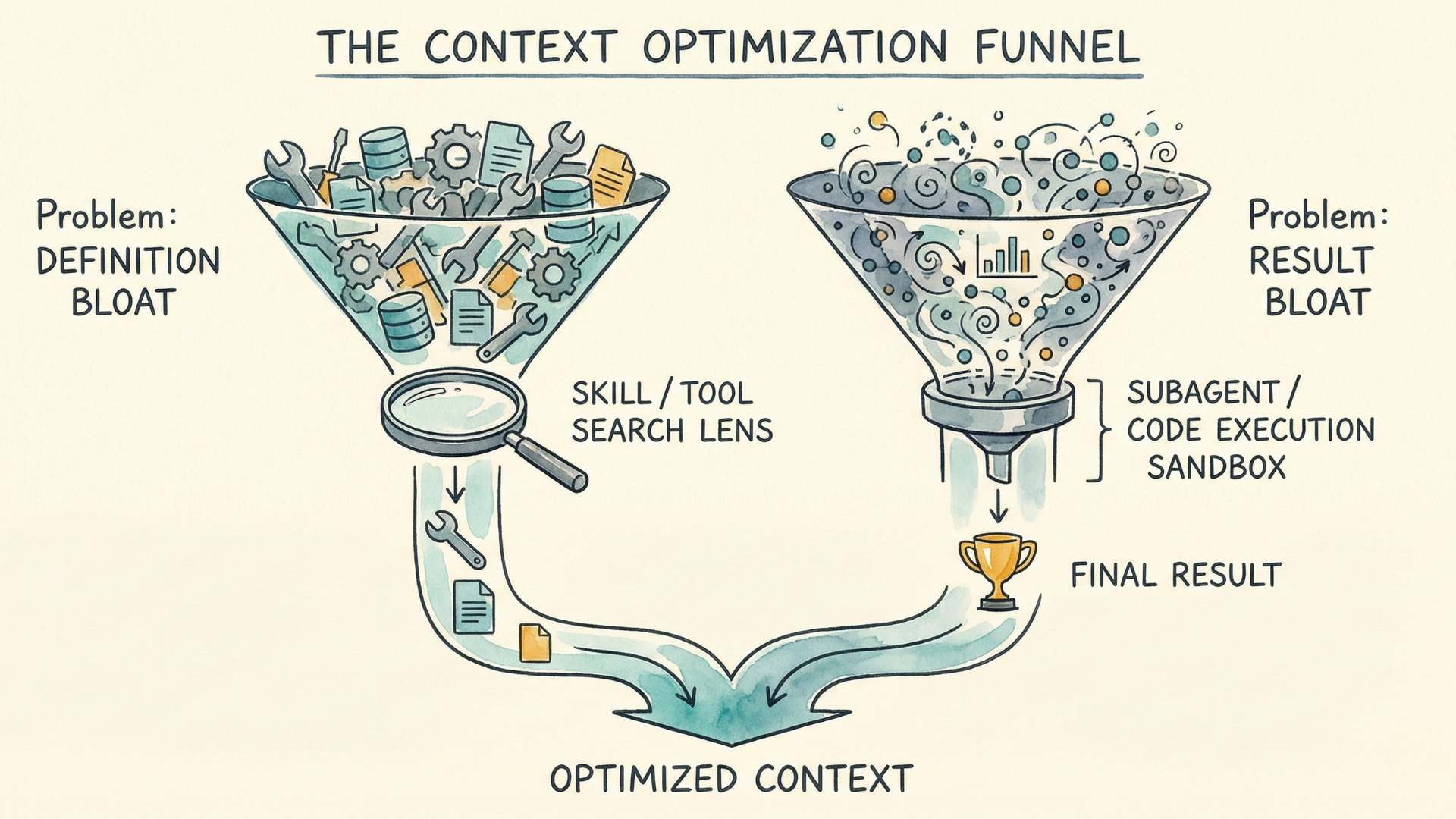

Two distinct problems are hiding here—and they require different solutions.

What's Slowing You Down?

Tool definition bloat hits when tools load everything upfront—whether through MCP or direct integrations. Without progressive disclosure, their full schemas, descriptions, and parameters enter context immediately. With many tools connected this way, there are cases where over two-thirds of a typical 200K context window gets consumed by tool definitions alone before the first message even starts.

Tool result bloat hits during execution. When Claude calls tools, results enter context. For multi-step workflows, these intermediate results accumulate—even when you only need the final conclusions.

Which problem are you facing? The answer determines your solution.

If Tool Definition Bloat Is the Issue

The principle: load when needed, not upfront.

Skills implement this through progressive disclosure—metadata loads first, full instructions load when relevant, reference files load on demand. We discussed Skills earlier for their portability and discoverability. Here we see their optimization benefit: progressive disclosure prevents definition bloat. A skill can be comprehensive without bloating every conversation because most of it stays unloaded until needed.

Tool Search Tool—a separate API feature from Anthropic—applies the same on-demand principle to tools. Instead of loading all tool definitions upfront, Claude searches for relevant tools when needed. Anthropic measured tool selection accuracy improving from 49% to 74% with search-based discovery—better results with less context consumed.

If Tool Result Bloat Is the Issue

The principle: return only final results that matter.

Traditional tool use means every result from the intermediary steps enters the context window. Claude calls an API, the response lands in context, Claude analyzes it, decides to call another tool, more results accumulate.

One solution is for Claude to write code scripts that handle the task orchestration—calling tools, processing data, computing the answer—and return only the final output. This is known as programmatic tool-calling. A budget compliance check that would load thousands of expense items instead returns: "3 employees exceeded budget: Alice, Bob, Carol." The mechanism could lead to 37% token reduction on complex research tasks. The trade-off is infrastructure—you generally need a sandboxed code execution environment, typically exposed to the agent as a tool it can invoke.

But that sandbox environment also gives you an opportunity to solve tool definition bloat together with result bloat. You can adapt the tool interface to present MCP servers as code APIs, so they become discoverable through filesystem exploration. This approach—code execution with MCP—combines programmatic tool-calling with on-demand tool discovery. You get both benefits: intermediate results stay in the sandbox (solving execution bloat) AND tool definitions load only when needed (solving definition bloat). Anthropic has shown cases where this combined mechanism led to 98.7% token reduction.

When You Also Need Specialized Reasoning

Programmatic tool-calling works when code can orchestrate the tools and compute the answer—like the budget compliance example above. That task requires multiple tool calls (fetch team members, get expenses for each, compare against budgets), but the logic between them is clear: no judgment needed, just follow the algorithm. But what about research, exploration, analysis—tasks where you can't specify the algorithm upfront because they require judgment at each step?

This is when Subagents come in handy. Subagents don't have to run in a sandbox infrastructure. But they operate in a separate context window. Tool definitions and intermediate results stay in the subagent's context, not yours—it returns only a condensed summary.

Subagents also enable specialization. Each subagent has its own system prompt—tuned instructions that steer its behavior toward a specific domain or task. A code-review subagent reasons differently than a research subagent because their prompts establish different expertise. This specialization is itself a form of optimization: a focused agent often performs better than a generalist trying to do everything.

So how do you choose between them? Both give you isolation—intermediate results don't bloat your main context, and you only get the final answer. The difference is what happens in that isolation: can code follow a clear algorithm, or does each step require LLM judgment?

If you can specify the logic upfront—fetch these records, filter by this condition, aggregate that way—use programmatic tool-calling. If the task requires reasoning throughout—research competitor pricing (what sources matter?), summarize a document (what's important?), analyze error logs (what patterns are significant?)—use a subagent.

The trade-off with subagents: they don't inherit your conversational context. They work best for self-contained tasks you can fully describe upfront.

For a deeper dive into the two context bloat problems and agent skills, see my companion article: The Two Context Bloat Problems Every AI Agent Builder Must Understand.

Distribute: How Do You Package It for Others?

Your capabilities are working. Your team wants them. Another project needs the same setup. Now what—copy files manually and hope nothing breaks?

Do You Actually Need a Plugin?

Not always. If you're working solo or iterating rapidly, standalone configuration works fine. Commands go in .claude/commands/, skills in .claude/skills/. Everything functions without packaging.

Plugins become valuable when you need distribution: team standardization (everyone uses the same commands and hooks), cross-project consistency (the same skill definitions everywhere), or public sharing (community members can install and benefit).

What Changes With a Plugin

When you package as a plugin, a few things change. Your /commit command becomes /my-plugin:commit—namespaced to avoid conflicts with other plugins. Instead of copying files between projects, teammates run claude plugin install. Versions are tracked with semantic versioning, and updates flow through claude plugin update.

A plugin bundles everything we've covered—commands, skills, subagent definitions, MCP configurations, hooks—into a single distributable package. The mechanisms inside work exactly the same; plugins add packaging and namespacing, not new capabilities.

The Practical Path

Start with Skills or Commands in the respective .claude/skills or .claude/commands directories, iterate until your capabilities work well. Note that Claude Code merged Commands into Skills in recent versions for simplicity—this makes sense if you realize both boil down to prompts and artifacts as context for the model. The difference is mainly that your commands can now also be automatically invoked like a skill. Other than that, the existing behavior is retained and our discussion still applies.

When you're ready to share, the conversion is straightforward: add a manifest in .claude-plugin/plugin.json, organize your components into the standard structure, and distribute.

Say you've built a code review workflow with a /review command, a skill that teaches Claude your team's conventions, and a hook that runs linting after every edit. Standalone, this lives in your project's .claude/ directory. To share it across your team's repositories, convert it to a plugin. Now everyone installs it once, gets updates automatically, and invokes it as /team-standards:review.

Plugins are the final phase in this progression. You've figured out what capabilities you need, how to run them, and how to keep them efficient—now you're packaging what works for others.

Putting It Together

Remember the questions that brought you here?

"Should I use Skills or MCP?" Both help you define capabilities, but they solve different problems. MCP connects Claude to external systems it can't already reach. Skills package instructions, code, and reference files for consistency and automatic discovery. They're not competing; they're complementary. You often use both together: MCP provides the connection, Skills provide the expertise.

"What's the difference between Skills and Subagents?" They address different phases. Skills help you define capabilities—they package expertise that's portable across execution contexts. Subagents help you optimize execution—they provide context isolation and enable specialization through tuned system prompts. Both can steer Claude toward specific domains, but Skills define what expertise exists (orthogonal to how it runs), while Subagents define how to execute (isolated context, specialized reasoning). They're not alternatives; they solve different problems in your project.

"Where do I put my instructions—CLAUDE.md or a Skill?" This involves both defining and optimizing. CLAUDE.md is always-on context—instructions that load in every conversation. Skills use progressive disclosure—they load when Claude determines they're relevant. Put foundational context (project standards, key conventions) in CLAUDE.md. Package specific capabilities into Skills to avoid bloating every conversation.

The primitives were never competing. Skills and MCP both help you define capabilities, but one packages expertise, the other provides connections to it. Skills and Subagents seem similar, but one is for defining, the other more for optimizing. The shift isn't memorizing categories—it's recognizing which problem each primitive solves.

Quick Reference

When New Primitives Appear

Claude Code will keep adding capabilities. When it does, you'll know how to place them: Does this help me define what Claude should do? Control how it runs? Optimize efficiency? Package for distribution? The Capability Lifecycle will help you understand where they fit—or recognize when something genuinely new has arrived.

And as a mental model, the Capability Lifecycle extends beyond Claude Code. You'll find the same four phases in OpenAI's Codex—AGENTS.md for always-on context, Custom Prompts for explicit invocation, Skills for auto-discovery, MCP for external connections. Cursor uses .cursor/rules and MCP. GitHub Copilot supports .github/copilot-instructions.md, AGENTS.md, and now Skills. The primitive names differ; the phases remain. If you understand the Capability Lifecycle, you'll navigate any of these agentic building tools faster—you're not dealing with new concepts each time, just mapping familiar phases to new implementations.

Additional Readings

- The Two Context Bloat Problems Every AI Agent Builder Must Understand — Agenteer

- Equipping agents for the real world with Agent Skills — Anthropic Engineering

- Advanced Tool Use — Anthropic Engineering

- Effective Context Engineering for AI Agents — Anthropic Engineering

- Code Execution with MCP — Anthropic Engineering

- Claude Code Documentation — Anthropic

- OpenAI Codex — OpenAI